The weak outlook for the global economy has rattled markets in 2022 as traders focused on the prospects of a near-term recession in many of the world’s advanced economies. Looking further ahead, however, the question is whether policymakers can bring inflation under control quickly enough to prevent a prolonged economic contraction.

At this year’s BNP Paribas Global Markets Conference APAC, guest economists, including former central bankers and policymakers, agreed that the US, Europe and Japan will all slide into recession in 2023 – but there will be differences around the depth and severity of the contractions.

Speaking at the November 21 event in Singapore, Sam Lynton-Brown, Global Head of Macro Strategy at BNP Paribas, noted that US interest rates will determine the direction of the US economy.

“The Fed has warned that interest rates will need to go higher before inflation falls back to its target range,” he said. “If inflation remains persistently high, rates will have to stay in restrictive territory for at least all of 2023, which will restrict GDP growth to below trend levels for a long time.”

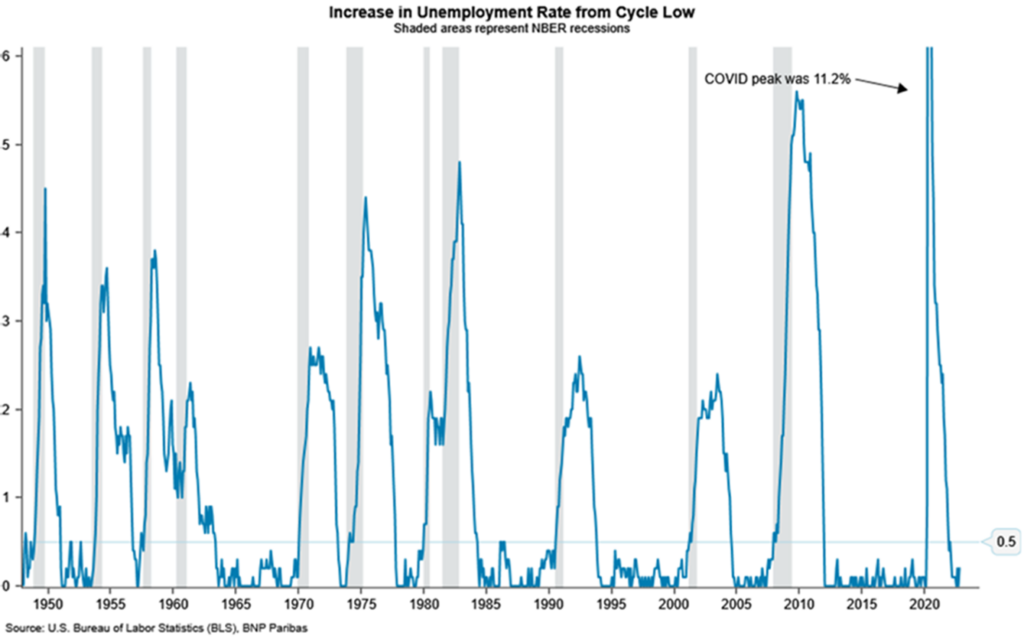

Speakers at the in-person conference noted that the Fed is projecting a rise in unemployment from 3.7% to 4.4% by the end of 2023. From 1945 to 2020, every increase of more than half a percentage point has been accompanied by a recession.

That tallies with corporate expectations. In a recent Conference Board survey, 98% of CEOs said they were preparing for a US recession over the next 12-18 months. An even higher percentage – 99% – said they were preparing for an EU recession.

How bad will it be?

Even if a recession in advanced economies is a virtual certainty, it is not yet clear how severe that contraction will be.

In the US, the depth of a recession will depend on how long it takes policymakers to bring inflation under control.

There is some good news: inflation is beginning to cool. The US consumer price index showed a 7.7% year-on-year increase in October – the smallest annual increase since January 2022.

At the BNP Paribas Global Markets event, however, guest speakers were united around the need for further rate hikes to bring prices under control.

The EU’s energy problem

The situation differs in Europe, both in terms of inflationary drivers and policy responses. After a massive energy price shock resulting from the abrupt termination of Russian gas supplies, the European Central Bank (ECB) hiked rates in July for the first time in 11 years. After successive increases in September and October, the key policy rate stands at 1.5%, the highest since January 2009.

Unlike in the US, wage inflation is not an issue in the EU. Negotiated pay rises are averaging around 3% – not enough to raise fears of a wage-price spiral. With consumer prices rising at 10.6% year-on-year in October, this modest rise is a 6% drop in real wages that is already affecting consumption.

Luigi Speranza, Head of Markets 360 and Chief Economist at BNP Paribas Global Markets, agrees the outlook is “challenging”.

“It looks like Europe is in for a tough time next year with the fight against inflation and high energy prices that are highly linked to a looming recession,” he said at the event in Singapore.

Japan the outlier

Japan is an outlier to the global trend of rising rates: it is one of the few countries still running an ultra-low interest rate monetary policy.

During its October meeting, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) maintained its key short-term interest rate at -0.1% and its rate for 10-year bond yields around 0%, but increased its 2022 inflation forecast to 2.9%.

Japan’s consumer inflation rate is increasing due to spikes of food and energy prices, exacerbated by the depreciating yen. The weaker currency will also hamper exports, raising expectations for a mild recession in the first half of 2023.

Despite a pick-up in inflation in 2022, there are no signs that the Bank of Japan is rethinking its approach. Japanese corporations remain reluctant to increase wages, and policymakers expect price rises to cool quickly in 2023.

Market participants, however, remain on watch for a change when BoJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s 10-year tenure ends in April next year.

“The anticipation that Japan’s monetary policy is set to change as inflation continues to make multi-decade highs and corresponds with Kuroda-san’s term at the BOJ coming to an end in 2023, is running very high indeed,” said Brian McCappin, Deputy Head of Global Markets APAC and Head of Institutional Sales APAC, BNP Paribas. “Clients are definitely looking for ways to trade and hedge this event into 2023.”